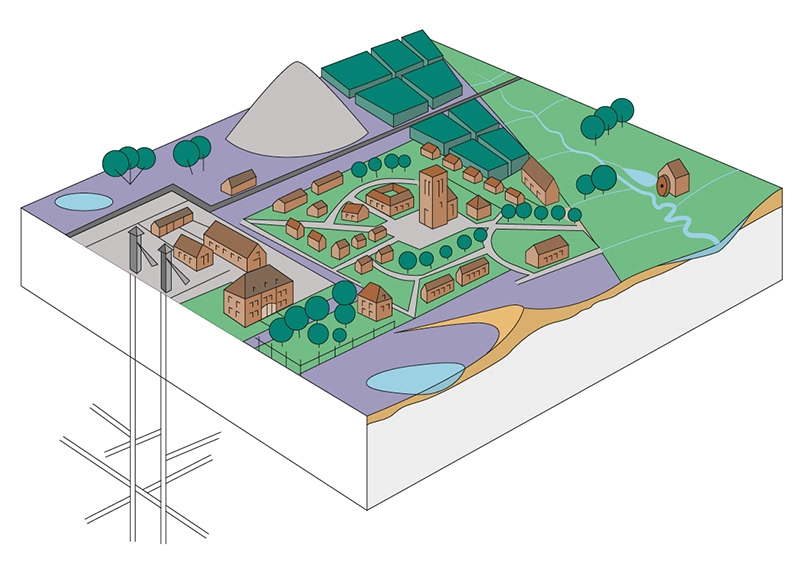

The Transition Landscape Atlas explores the post-mining landscape of Hoge Kempen to trace how the design space of its ‘heritage-development’ is staged. It starts from the UNESCO nomination for this landscape which describes it as a unique material document of the transition between rural and industrial modes of production. Heather fields, creeks, forest estates and water mills stand next to the industrial heritage of three former mines, with slag heaps and garden cities. The story of the transition as heritage is strongly connected to the intangible landscape: the migration history of garden cities that hosted thousands of workers coming from South and East of Europe and North of Africa. The mining sites closed by the 1980s and were eventually repurposed as a cultural centre, technology park and art museum, while the garden cities were designated as established architectural heritage. In the UNESCO nomination, the authors underline the landscape hybridity as a particular value to be preserved for the future - not just as a feature of tangible patrimony, but also as a heritage of migration and encounters of different cultures.

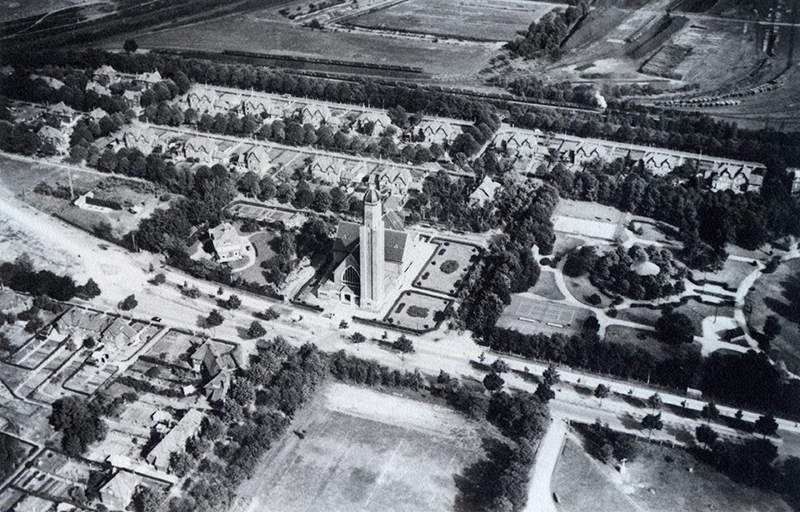

The atlas explores how the past travels to the design space of this landscape in relation to contemporary challenges - those of balancing between heritage conservation, economic development and the urgency of sustainable transition. It zooms in on how these challenges emerge through specific concerns in the garden city of Waterschei, a neighbourhood in the city of Genk. In doing so, the atlas focuses on two landscape ‘things’ as sites of tensions between different perspectives on the values of heritage and development. These two things are ‘garden city houses’ and ‘rows of trees’, both evaluated as elements of a heritage ensemble3. By tracing the tensions that emerge around the future of these two things, the atlas explores how ‘development’ is staged as a vision for the future, as well as how it is challenged through practices in the historical landscape: How is the image of a ‘transition landscape’ produced and maintained? How is its design space shaped by engaging with the past? What is allowed to enter this space, and what is hindered from doing so?

Hoge Kempen Rural-Industrial Transition Landscape.

More info at: whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5623/

Image by Johan Van Den Bosch.

Transition Landscape Atlas.

2022. Video still showing the Waterschei former mine site.

Transition Landscape Atlas. 2022. Video still showing the Waterschei terril (slag heap).

Not only the people changed, but the environment also changed. Mine buildings were placed, the mine shafts. The mine was lifted deep out of the ground and the waste, the stones, were placed in a pile, which now forms our slag heaps.

(Jef Gabriels, mayor of Genk, 1987-2009)

Waterschei garden city - aerial photo (image by Heidebloemke Heemkring).

Determining heritage elements in urban planning are the circulation patterns (access loops, residential streets, walking paths and communal inner areas, curved streets), the location of the housing groups... The architectural quality is determined by unity in style and materiality between the different types (linked single-family houses, guest houses, collective facilities in traditionally inspired brick architecture). Source: Onroerend Erfgoed Inventaris, Steenkoolmijn van Waterschei: Tuinwijk inventaris.onroerenderfgoed.be/erfgoedobjecten/122160

Transition Landscape Atlas. 2022. Video still showing the Opglabbekerzavel natural area with a hayfield in Waterschei.

Transition Landscape Atlas. 2022. Video still showing the As terril (slag heap).